1. The Swift Language

A Swift script describes data, application components, invocations of applications components, and the inter-relations (data flow) between those invocations.

Data is represented in a script by strongly-typed single-assignment variables. The syntax superficially resembles C and Java. For example, { and } characters are used to enclose blocks of statements.

1.1. Conventions

The following conventions will be used throughout the guide:

-

Swift source listings will appear in the following form:

// Swift script code -

When describing syntax, the code will appear as follows:

<rule> := <definition>The following conventions are used for syntax blocks:

-

Angle brackets indicate a labeled item that is to be substituted when writing actual code:

<variableName>can be used to meana,b,myVariable, etc. -

Square brackets indicate optional items:

[something optional] -

Single quotes indicate a literal character or string when the literal could otherwise be interpreted as being part of a special syntax symbol:

'['means a literal left square bracket and not the beginning of an optional item. -

The pipe symbol is used to indicate two or more mutually exclusive choices:

A | C | Bmeans eitherAorBorC. -

Parentheses are used for groupping

-

The asterisk (

*) is used to indicate zero or more repetitions of the operand immediately to the left. For example,A*signifies that the letterAcan appear any number of times, including not at all. -

A plus sign (

+) is used to indicate one or more repetition(s)

-

Examples:

[<this is something optional>]

<first alternative> | <second alternative>

(<first> <alternative>) | <second alternative>

<this can be repeated any number of times including none>*

<one or more of these are possible>+1.2. Values

Values in Swift are the most basic form of data. All values have an associated

type. Examples of values are 1.0, "a string", etc.

1.3. Variables

Swift variables are symbols that hold values. Variables have a type, which is specified when the variable is declared. It is also possible to assign a value to a variable when the variable is declared. A variable declaration has the following syntax:

<type> <name> [= <value>];It is also possible to declare multiple variables of the same type in one line:

<type> <name> [= <value>] (, <name> [= <value>])*Examples:

int a;

string message = "A message";

int c = 1, d = 2;Variables must be assigned a value exactly once. The following Swift program will result in compile-time errors:

int a = 2;

a = 3;  int b;

f(b);

int b;

f(b);

| Error: variable "a" can only be assigned once | |

| Error: variable "b" is not initialized |

1.3.1. Types of Variables

There are two types of variables:

- Local variables

-

Local variables are “normal” variables which can be declared in any scope using variable declarations as shown above.

- Global variables

-

Global variables are variables that are declared in the main scope and are visible in all the scopes in a Swift program. Their declaration is prefixed with the keyword

globalas shown below:Global Variableglobal <declaration>;Example:

global float PI = 3.14159;

1.3.2. Scoping Rules

There are three types of scopes: the main scope, function scopes, and sub-scopes. Variables declared in a scope are always visible within that scope, regardless of whether they are declared lexically before use or not.

- Main scope

-

The global scope is the top-level scope of a Swift program. Global variables can only be declared in the main scope.

- Sub-scopes

-

Sub-scopes are scopes introduced by code blocks, which are sections of code surrounded by curly brackets (

{…}) with the exception of function scopes. Sub-scopes create a hierarchy. Each sub-scope has a parent, which may, in turn, have its own parent. A variable declared in a scope is visible in all of its sub-scopes and then recursively visible in all sub-scopes of each sub-scope. A variable declared in a scope cannot be re-declared in a sub-scope. In other words, shadowing is not allowed:int a = 1; if (true) { int a = 2; // Illegal: shadowing is no allowed }Whenever a variable is referenced in a scope, the Swift compiler will search for the corresponding variable declaration starting with the scope from which the reference is made and, if not found, continue recursively with all ancestor scopes until a declaration is found. Function scope:: A function scope is the scope of the body of a function declaration. The following are visible in a function scope: global variables, the formal parameters of the function, and variables declared within the function body. A function scope can have its own sub-scopes.

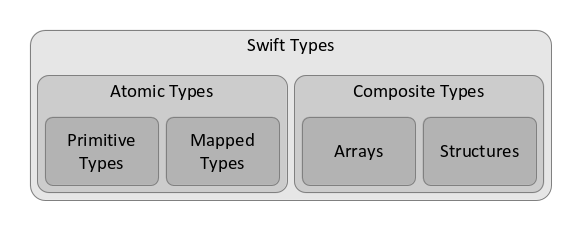

1.4. Types

Types in Swift can be atomic or composite. An atomic type can be either

a primitive type or a mapped type. Swift provides a fixed set of primitive

types, such as integer and string. A mapped type indicates that the actual

data does not reside in CPU addressable memory (as it would in conventional

programming languages), but in POSIX-like files. Composite types are further

subdivided into structures and arrays. Structures are similar in most

respects to structure types in other languages.

1.4.1. Primitive Types and Values

A primitive type is a type that represents a single item stored in internal

memory. The primitive types in Swift are int, string, float, and boolean.

int

The int type represents a 32 bit integer. Integer value literals are of the

form:

['+'|'-']<digit>+Examples:

int a = +1;

int b = -2;

int c = 9999999;string

A string represents a sequence of characters. String literals are enclosed in double quotes and have the following form:

'"'(<stringCharacter> | <escapeSequence>)*'"'Where <string character> is any character except double quotes or a backslash

('\'), and

<escape sequence> := '\' ('n' | 'r' | 't' | 'b' | 'f' | '"' | '\')The following table lists the meaning of the escape sequences:

| Sequence | Meaning |

|---|---|

|

a literal backslash |

|

new line (ASCII code |

|

carriage return (ASCII code |

|

tab (ASCII code |

|

backspace (ASCII code |

|

form feed (ASCII code |

|

a literal double quote character |

Examples of string literals include:

string a = "A string";

string b = "A string containing a \n newline";

string c = "\"A string in quotes\"";float

Floats represent a double precision (64 bit) floating point number. Float literals have the following syntax:

['+'|'-'] <digits> '.' <digits> [('e' | 'E') ['+'|'-'] <digits>]Example:

float a = 1.0;

float b = -1.2e-3;

float c = 2e50;boolean

A boolean represents a truth value. Boolean literals are either true or

false.

boolean a = true;

boolean b = false;1.4.2. Mapped types

Mapped types are types that represent data that resides in a (single) file. They can be thought of as file references (or pointers to files). Users can define any number of mapped types to distinguish between different types of files used in a Swift program. A mapped type can be defined as follows:

type <typename>;When declaring a mapped type, an optional mapping can be specified in order

to describe the location of the file represented by a variable. The following

example declares a mapped type and variable that points to a file named

input.txt:

type image;

image input <"input.txt">;|

|

See also: File Mapping, Mapper Library, External Type |

1.4.3. Structures and Structure Expressions

Structures are types that can be used to encapsulate a fixed number of fields and are similar to structures in C. A structure’s fields can mix primitive, mapped and composite types. The syntax for declaring a structure is as follows:

type <structName> {

[<type> <fieldName>;]+

}Fields in a structure can be accessed as follows:

<variable>.<fieldName>The following example declares and uses a structure named Employee that holds

some basic data of a hypothetical employee:

type employee {

string name;

int id;

string location;

}

employee e;

e.name = "John Doe";

e.id = 1000;

e.location = "Room 1401";It is also possible to initialize structure variables using a structure expression. The syntax of a structure expression is:

{ (<key>: <value>)* }The last part of the employee example above can be simplified to:

employee e;

e = {name: "John Doe", id: 1000, location: "Room 1401"};|

|

See also: readData(), writeData(), read(), write() |

1.4.4. Arrays and Array Expressions

Swift arrays are data types that contain a variable number of items of the same type. Each item in an array has an associated key or index. Arrays can be declared as follows:

<itemType> '[' <keyType> ']' <arrayVariableName>;Key types are restricted to primitive types. If the keyType is omitted, it

defaults to int:

<itemType> '[]' <arrayVariableName>;

// this is equivalent to

<itemType> '[' int ']' <arrayVariableName>;Arrays in Swift are automatically grown to accommodate the number of items stored in them. Additionally, arrays are sparse. In other words, array keys can be arbitrary values (as long as they match the declared key type).

Array items are accessed using the following syntax:

<arrayVariableName> '[' <keyValue> ']'For example, the following snippet of code declares an array with int keys

(the default) which stores string values and adds a few items to it:

string[] array;

array[0] = "Zero";

array[2] = "Two";

array[100] = "One hundred";The following is an example of an array with strings as key values:

float[string] constants;

constants["PI"] = 3.14159;

constants["e"] = 2.71828;If the item type is a structure type, Swift allows a “slicing”

access mode that produces an array with all the values of a particular field of

the item type and with the same key type as the key type of the array. The

syntax is the same as for structure field access. In other words, if s is a

structure containing some field f, and if a is an array of s, then the

following are equivalent: a[<index>].f and a.f[<index>]. Example:

type myStruct {

int a;

float b;

}

myStruct[] array = [{a: 1, b: 0.1}, {a: 2, b: 1.6}];

f(array.b);

Invokes function f with an float[] array equal to [0.1, 1.6].

|

Alternative ways of initializing arrays are: array expressions, sparse array expressions, and range expressions.

Array Expressions

Array expressions have the following basic syntax:

'[' [<value> (, <value>)*] ']'When array expressions are used, indices are automatically created by Swift, starting from zero for the first array item and incrementing by one for each subsequent element:

string[] array = ["Zero", "One", "Two"]

trace(array[0]); // "Zero"

trace(array[1]); // "One"

trace(array[2]); // "Two"Sparse Array Expressions

Sparse array expressions can be used to initialize an array with values that correspond to non-consecutive or non-integer keys. The syntax of a sparse array expression is:

{ [<key>: <value> (, <key>: <value>)*] }Examples:

float[string] constants;

constants = {"PI": 3.14159, "e": 2.71828};

string[] orders;

orders = {1: "One", 10: "Ten", 100: "Hundred", 1000: "Thousand"};Range Expressions

Range expressions are compact way of describing arithmetic sequences. The syntax is:

'[' <from>:<to>[:<step>] ']'A range expression returns an array containing the sequence of numbers starting

at <from>, with the last element not greater than <to> and with a difference

if <step> between two consecutive elements. The parameters must be numeric

literals. If they are integers, then the returned array has type int[] and

the step is optional (assumed to be 1 if missing). If the parameters are

float literals, the type of the range expression is float[] and the step is

mandatory. The actual implementation generates lazy arrays for range expressions.

Example:

int[] a = [1:4]; // a = [1, 2, 3, 4]

int[] b = [1:6:2]; // b = [1, 3, 5]

int[] c = [0.0:10.0:3.33]; // c = [0.0, 3.33, 6.66, 9.99]|

|

See also: Auto Key Type |

1.4.5. Special Types

Special types are types that do not fall neatly into any of the above categories.

There are two special types in Swift: auto and external.

The Auto Type

The auto type is used as a special array index type. Arrays declared

with an auto key type can be constructed progressively, without regard

to what particular value the index for an item will be. It is used

in conjunction with the append operator (<<). The

auto type does not have associated literal values, and items in an

array declared with auto indices cannot be accessed randomly. Certain

operations, such as the foreach statement,

can be used to associate a variable of type auto with an opaque value

that can be used to refer to items in arrays with auto keys. The

following example attempts to clarify this:

int[auto] a;

a << 1;

a << 2;

a << 4;

a << 8;

int[auto] b;

foreach value, key in a {

b[key] = a[key];

}

// b is now an exact copy of aThe external type

The external type is a special type of mapped type. It tells Swift to suspend

its normal file management when dealing with variables of type external (see

File Management). This is

distinct from Swift’s [runtime:order-of-operations], dependency tracking

mechanism>>, which remains in effect. The purpose of the external type is

to expose otherwise hidden dependencies to Swift in order to ensure correct

functioning of a script.

1.5. Mapping Declarations

Variables with a mapped type or a composite type containing mapped types will have an associated physical file for every mapped value. Mappers allow a user to specify how mapped values are associated with physical files. Mappers are specified as part of the variable declaration as follows:

<type> <name> '<' <mapperName>; [<mapperParameters>] '>';where

<mapperParameters> := <name> = <value> (, <name> = <value>)*Mapper parameters can be specified in any order. Certain mapper parameters are mandatory, while others can be omitted and assume default values.

Example:

type file;

file inf <SingleFileMapper; file = "input.dat">;As a shortcut, it is possible to use a string literal when only one mapped value (or file) is involved. The previous example is equivalent to:

type file;

file inf <"input.dat">;The usefulness of mappers becomes more obvious when more complex data structures are involved. A number of mappers support deeply nested data structures and arrays. These can be used to automatically provide a mapping between non-trivial collections of files and Swift variables.

If a variable of a mapped type is declared without an explicit mapping declaration, Swift will default to using the ConcurrentMapper, which automatically assigns temporary files to mapped values.

|

|

See also: File Mapping, Mappers. |

1.6. Expressions

Expressions are pieces of code that produce a value as a result. Previous sections already contain a few examples of expressions, namely array expressions, structure expressions, and range expressions. In addition to that, value literals are also expressions. What follows is a description of all expression types in Swift:

- Primitive type literals

-

Also called constants, these are literal values corresponding to Swift’s primitive types. They are described in the section about primitive types and values.

- Variable references

-

Variable references produce the values currently stored in the referenced variable. When a variable name is used in an expression context, Swift applies the scoping rules to determine the particular variable to be used and produces its value.

- Array expressions

-

Used to construct array values. See array expressions.

- Sparse array expressions

-

Used to construct array values with sparse keys. See sparse array expressions.

- Range expressions

-

Produce arrays containing arithmetic series. See range expressions.

- Structure expressions

-

Used to construct structure values. See structure expressions.

- Array subscript references

-

Similar to variable references, array subscript expressions are used to obtain the value of a particular item in an array.

- Structure field references

-

Produce the value stored in a field of a structure-typed variable or, in the case of the structure array references, an array with values stored in a field of a structure-typed variable.

- Function expressions

-

Function expressions produce the result of the application of a function to some parameters. For details, please see the section about functions.

- Operator expressions

-

Operator expressions differ from function expressions in syntax and in that, unlike functions, operators are not user-defineable. For details, see the section on operators.

1.7. Operators

Swift provides a standard set of arithmetic and logic operators. There are two types of operators: unary and binary. Unary operators are operators that have a single operand. They are used in prefix notation:

<unaryOperator> <operand>Binary operators have two operands and are used in infix notation:

<operand> <binaryOperator> <operand>Each operator has a precedence level. If two or more operators with the same

precedence level appear consecutively in an expression, the expression is

evaluated from left to right. In the following example, <op1> is evaluated

first, followed by <op2>:

<value1> <op1> <value2> <op2> <value3>Specifically, <value1> <op1> <value2> is calculated, yielding

some value which we will call <intermediate>. The value of the entire

expression will then be <intermediate> <op2> <value3>:

This behavior can be modified by using parentheses, which ensure that their

contents is evaluated as a standalone sub-expression. In the previous example,

parentheses can be used to force the evaluation of <op2> first:

<value1> <op1> '(' <value2> <op2> <value3> ')'If two or more consecutive operators have different precedence levels, then the

operators are evaluated in the order of their precedence, starting with the

lowest level. For example, multiplication has a lower precedence level than

addition, so the following expression evaluates to 7 rather than 8:

1 + 2 * 3The following table lists the precedence level of Swift operators:

| Level | Operator(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

1 |

|

Logical negation |

1 |

|

Negation operator |

2 |

|

Multiplicative operators |

3 |

|

Additive operators |

4 |

|

Relational operators |

5 |

|

Equality operators |

6 |

|

Logical AND |

7 |

|

Logical OR |

The types of the operands are relevant, and there may exist multiple

implementations for an operator, depending on the types of the operands. For

example, the addition operator, \+, can either add integers or floating point

numbers, and the type of the resulting value will depend on the type of

operands. When describing operators, the operand types and result types are

indicated using the following syntax:

<unaryOperator> <operandType> -> <resultType>

<operandType> <binaryOperator> <operandType> -> <resultType>The unary operators in Swift are:

-

! boolean -> boolean -

Logical negation operator.

-

- int -> int -

Integer negation operator.

-

- float -> float -

Float negation operator

The binary operators are:

-

int * int -> int -

Integer multiplication

-

float * float -> float -

Floating point multiplication

-

int * float -> float -

Floating point multiplication. The integer operand is first converted to a float and then the multiplication is performed as with

float * float -> float. -

float * int -> float -

Same as above.

-

int / int -> float -

Floating point division. The operands are first converted into floats and then the division is performed. For example, the result of

3 / 2is1.5. -

float / int -> float,int / float -> float,float / float -> float -

Same as above except that for operands that are already

float, no conversion is necessary. -

int %/ int -> int -

Integer division. Evaluates the quotient of the division of the first operand (divisor) with the second operand (dividend). The quotient is defined as the number with the largest absolute value such that

|quotient * dividend| < |divisor|.The quotient is negative if the divident and divisor have opposite signs. Example:

int q1 = 5 %/ 2; // 2 int q2 = -7 %/ 2; // -3 -

int %% int -> int -

Integer remainder. The result of this operation is a number,

r = (a %% b), such that(a %/ b) * b + r = a -

float %% float -> float -

Floating point remainder. The result of

a %% bis a floating point numberr, such thatr = a - (b * q), where q is an integer whose magnitude is as large as possible while satisfying|b * q| < |a|. -

int + int -> int -

Integer addition. Self explanatory.

-

float + float -> float,float + int -> float,int + float -> float -

Floating point addition. Also self explanatory.

-

string + any -> string,any + string -> string -

String concatenation. Evaluates to a string formed by concatenating the string representation of the first operand with the string representation of the second operand.

-

int - int -> int -

Integer subtraction

-

float - float -> float,float - int -> float,int - float -> float -

Floating point subtraction.

-

int < int -> boolean,float < float -> boolean -

Less than. Evaluates to

trueif the first operand is strictly less than the second operand. Otherwise it evaluates tofalse. -

int <= int -> boolean,float <= float -> boolean -

Less or equal. Evaluates to

trueif the first operand is less than or equal to the second operand. Otherwise it evaluates tofalse. -

int > int -> boolean,float > float -> boolean -

Greater than. Evaluates to

trueif the first operand is strictly greater than the second operand. Otherwise it evaluates tofalse. -

int >= int -> boolean,float >= float -> boolean -

Greater or equal. Evaluates to

trueif the first operand is greater than or equal to the second operand. Otherwise it evaluates tofalse. -

any == any -> boolean -

Equals. Evaluates to

trueif the operands are equal. If one of the operands is anintand the other afloat, theintis first converted to afloatafter which thefloatvalues are tested for equality. -

any != any -> boolean -

Not equals. The result of

a != bis the same as the result of!(a == b). -

boolean && boolean -> boolean -

Logical AND. Evaluates to

trueif and only if both operands aretrue. -

boolean || boolean -> boolean` -

Logical OR. Evaluates to

trueif at least one operand istrue.

1.8. Program Structure

A general swift program has the following structure:

<importStatement>*

(<statement> | <functionDeclaration>)*1.8.1. The Import Statement

The import statement can be used to bring definitions from an external Swift

source file into the current program. The syntax is:

import '"' <target> '"';where <target> is the path to a .swift file without extension.

For example:

import "/usr/local/swift/lib/constants";

import "../lib/functions";

import "defs";If a relative path is specified as a target, Swift will attempt to resolve the

file using directory in which the current Swift script is running. If the

target is a plain file name, Swift will first look for the corresponding file

in the current directory. If no such file is found in the current directory,

Swift will attempt to find the file in directories specified using the

SWIFT_LIB environment variable. The SWIFT_LIB variable can contain one or

more directories separated by the system’s path separator character (":" in

Linux / OS X and ";" in Windows).

Example:

export SWIFT_LIB=${HOME}/swift/defs:${HOME}/swift/functions1.9. Functions

Functions represent code abstractions. They can have zero or more formal parameters (or formal input parameters) and zero or more formal return parameters (or formal output parameters).

1.9.1. Function Declarations

Functions are declared using the following syntax:

<formalOutputParams> <name> '(' <formalInputParams> ')' {

<statements>

}

<formalOutputParams> := [ '(' <type> <name> (, <type> <name>)* ')' ]

<formalInputParams> := [ <formalInputParam> (, <formalInputParam>)* ]

<formalInputParam> := <type> <name> [ = <primitiveValue>]1.9.2. Function Invocation

A function is “applied” or used through a function invocation. When a function is invoked, a number of actual parameters is supplied. They must correspond to formal parameters in the function declaration. A function invocation has the following form:

[<actualOutputParams>] = <name>(<actualInputParams>);

<actualOutputParams> :=

<lvalue> | '(' <actualOutputParam> (, <actualOutputParam>)* ')' ]

<actualOutputParam> := [<type>] <lvalue> [ = <name>]

<actualInputParams> := [ <positionalParams> , ] [ <keywordParams> ]

<positionalParams> := <expression> (, <expression>)*

<keywordParams> := <name> = <expression> (, <name> = <expression>)*Alternatively, functions with a single return argument can be invoked as part of a function invocation expression:

<name> '(' <formalInputParams> ')'The following example shows a function definition and invocation:

(int result) add(int a, int b) {

result = a + b;

}

int sum = add(1, 5);Both output and input parameters are optional. The following example declares and invokes a function with no output parameters:

printMessage(string msg) {

trace("Message: ", msg);

}

printMessage("Hello world!");Correspondingly, the following example declares and invokes a function with no input parameters:

(int result) one() {

result = 1;

}

int n = one();As hinted by the function declaration syntax, input parameters can have a default value, in which case they become optional parameters. Optional parameters can be omitted when a function is invoked, in which case they assume the default value specified in the function declaration. If specified, an optional argument must be passed as a keyword actual parameter. Keyword parameters are said to be passed by name.

Example:

(int result) increment(int n, int amount = 1) {

result = n + amount;

}

int a = 10;

int b = increment(a);  int c = increment(a, amount = 2);

int c = increment(a, amount = 2);

the default value for amount is used, so b will be 11

| |

c will be 12

|

1.9.3. Parameter Binding

The are a number of rules that govern the binding of actual parameters to formal parameters. If a function has more than one formal output parameter, then the binding can be done either positionally or by name, but the two cannot be mixed. If parameters are passed by name, the order in which actual output parameters are specified can be arbitrary. The following example illustrates both options:

(int a, int b, int c) f() {

a = 1;

b = 2;

c = 3;

}

// positional binding

int a1, b1, c1;

(a1, b1, c1) = f();

// keyword binding

int a2, b2, c2;

(c2 = c, b2 = b, a2 = a) = f();Additionally, actual output parameters can be declared as part of the function invocation:

(int a3, int b3, int c3) = f();As seen previous, input parameters can also be passed possitionally or by name. In particular, optional parameters must always be passed by name. The two method can be mixed with the following restriction: parameters passed positionally must be specified first. In other words, no positional parameters are allowed after a keyword parameter. As is the case with named output parameters, the order in which named input parameters are passed is not relevant.

Example:

(int result) addFour(int a, int b, int c, int d = 1) {

result = a + b + c + d;

}

int r1 = addFour(d = 4, c = 3, b = 2, a = 1);

int r2 = addFour(1, 2, d = 4, c = 3);By contrast, the following invocations of addFour are illegal:

int r3 = addFour(1, 2, 3, 4);  int r4 = addFour(a = 1, 2, 3, d = 4);

int r4 = addFour(a = 1, 2, 3, d = 4);

Illegal: parameter d is optional and must be passed by name

| |

| Illegal: positional parameters follow a named parameter |

1.9.4. Application Functions

Application functions are a mechanism to give command-line applications the appearence of a Swift function. This allows a Swift program to invoke a command line application as if it were a normal Swift function. Application functions are declared as follows:

app <formalOutputParams> <name> '(' <formalInputParams> ')' {

<applicationName> <commandLineArgument>* <redirectSpecification>*;

}

<applicationName> := <identifier> | <stringLiteral>

<commanLineArgument> := <expression>

<redirectSpecification> := (stdout | stderr | stdin) = <expression>The formal parameters have the same form as in the case of normal function declarations.

The <applicationName> can either be a string naming a path to an executable

(or just an executable), or an identifier that will be

resolved by the Swift run-time to an

executable.

The expressions for the command line arguments must evaluate to primitive values, which will be converted by Swift to strings and passed as the application’s command line.

The expressions for standard stream redirects must be of type string and name

files in/from which the applications' streams will be redirected.

Example:

app (file outf) sort(file inf, int field) {

sort "-k" filename(inf) stdout = filename(outf);

}|

|

See also: Application Functions Execution |

1.10. Statements

Statements in Swift are entities that express relationships between data.

1.10.1. Assignment Statement

The assignment statement associates a declared variable or structure member of a declared variable or an array item of a declared variable with the result of an expression (“expression” may sound fancy, but it includes primitive literals). The syntax for the assignment statement is:

<lvalue> = <expression>;

<lvalue> := <variable> (<arrayIndexAccessor> | <structFieldAccessor>)*

<arrayIndexAccessor> := '[' <index> ']'

<structFieldAccessor> := '.' <fieldName>LValues

Examples:

int a, b, c;

int[] v;

a = 1;

b = a + 2;

c = abs(-b);

v[1] = a;

v[2] = b;1.10.2. Append Statement

<array> '<<' <expression>;Example:

int[auto] a;

a << 1;

a << 2;

a << 4;1.10.3. If Statement

The if statement allows the expression of conditional data relationships based on the value of some arbitrary boolean expression. The syntax is:

<ifStatement> :=

if '(' <booleanExpression> ')' <thenBlock>

[

(else <elseBlock>)

|

(else <ifStatement>)

]

<thenBlock> := <statementBlock>;

<elseBlock> := <statementBlock>;

<statementBlock> := { <statement>* }If <booleanExpression> evaluates to true, then <thenBlock> takes effect.

If <booleanExpression> evaluates to false, then there are two choices,

depending on whether an the exact form of the else part:

-

elseis followed by an<ifStatement> -

the nested if statement is evaluated

-

elseis followed by<elseBlock> -

<elseBlock>takes effect. -

no

elsepart is specified -

the effect of the overall

ifstatement is the same as if no statement was present at all.

Example:

int x = ...;

int step, sign;

if (x >= 0) {

step = 1;

}

else {

step = 0;

}

if (x > 0) {

sign = 1;

}

else if (x < 0) {

sign = -1;

}

else {

sign = 0;

}1.10.4. Switch Statement

The switch statement is a convenient way of expressing conditional relationships based on multiple possible values of an expression. The syntax is:

switch '(' <expression> ')' {

( <case> | <default> )*

}

<case> :=

case <caseExpression>: <caseStatements>

<default> :=

default: <statements>

<caseExpression> := <expression>

<caseStatements> := <statements>The switch statement tests the value of the expression successively against

<caseExpression>. Once a match is found, the corresponding <caseStatements>

are evaluated. If none of <caseExpression> are equal to the switch expression,

and if a <default> is present, the statements corresponding to <default> are

evaluated.

If two or more case expressions evaluate to the same value, and if the switch expression is equal to that value, only the statements for the first case will be evaluated.

1.10.5. Foreach Statement

The foreach statement allows parametrization of statements based on the values (and optionally keys) of an array:

foreach <valueVariable> [, <indexVariable>] in <expression> {

<statements>

}The <expression> must be of array type. The foreach

statement evaluates the contained <statements> for each value stored in the

array. At each evaluation the value is bound to the <valueVariable>. If a

<indexVariable> is also specified, the corresponding array index will be bound

to it. The types of <valueVariable> and <indexVariable> are automatically

inferred by the Swift compiler from the type of <expression> and they do not

need to be declared separately. By default, foreach parallelizes the

evaluation of <statements> as much as possible. For details about that, see

Arrays and Iterations.

Here is an example foreach statement without an index variable:

int[] squares;

foreach x in [0:16] {

squares[x] = x * x;

}And one which does use the index variable:

int[] a = ...;

int[] b;

foreach value, index in a {

b[index] = value;

}1.10.6. Iterate Statement

The iterate statement can be used to implement convergence algorithms in

which a set of statements is evaluated repeatedly until a certain condition

is met. A counter is provided to distinguish between the evaluation steps. The

iterate statement has the following form:

iterate <indexVariable> {

<statements>

} until '(' <expression> ')';The <indexVariable> is an integer typed variable and it does not need to be

declared separately. Its initial value is 0. The <expression> must evaluate

to a boolean value. The iterate statement performs the following steps:

-

Initialize

<indexVariable>to0 -

Evaluate

<statements> -

Increment

<indexVariable> -

Evaluate

<expression>. If it istrue,iteratecompletes. -

Go to step 2

Example:

vector b = ...;

vector[] a;

a[0] = initialGuess();

iterate i {

vector nextGuess = computeNextVector(a[i], op(a[i]));

a[i + 1] = nextGuess;

} until (error(b, op(nextGuess)) < 0.1);The termination expression may depend on the index variable or variables

declared inside the body of iterate. However, the values of the latter will

reflect the values calculated as part of the last evaluation of the body, and

may not reflect the incremented value of the iteration variable. The following

example illustrates this issue:

iterate i {

trace(i);  } until(i == 1);

iterate i {

trace(i);

} until(i == 1);

iterate i {

trace(i);  int j = i;

} until(j == 1);

int j = i;

} until(j == 1);

Will print 0

| |

Will print 0 and 1

|

In the first case, i starts as 0, the trace is evaluated (and prints a

0), then i is incremented to 1 and the termination condition is evaluated.

The termination condition will be true on the first evaluation.

By contrast, in the second case, during the first evaluation of the body, the

variable j is assigned the initial value of i, which is 0. The index

variable, i, is then incremented to 1. However, the termination expression

refers to j, whose last value is 0, and therefore it evaluates to false.

2. The Swift Library

The Swift runtime library consists of a collection of functions and mappers. There are two versions of the standard library:

- Version 1

-

This is currently the default library and nothing special needs to be done to use it. Version 1 of the library will be phased out in future versions of swift unless the following import statement is used:

import "stdlib.v1"; - Version 2

-

This is a more extensive library. It will become the default in future versions of Swift. It can be used with the current version by importing it explicitly:

import "stdlib.v2";

The mapper library is unaffected by the choice of standard library.

2.1. Standard Library V1

2.1.1. Summary

2.2. Standard Library V2

2.2.1. Summary

2.3. Mapper Library

2.3.1. Summary

<SingleFileMapper; string file>Maps a single physical file to a file-valued variable.

Parameters:

- file

-

A relative or absolute path or a URL specifying the file location.

Example:

file f <SingleFileMapper; file = "input.txt">;This is equivalent to:

file f <"input.txt">;

<SimpleMapper; string location = ".", string prefix = "", string suffix = "",

string pattern = "*", int padding = 4, string separator = "_">Allows mapping of variables of arbitrary types. The file names are detemined by concatenating the structure field names and array indices of a fully qualified leaf value. Given a variable of some arbitrary type, a particular leaf is referenced as:

<name> (<field> | <index>)*

<field> := '.' <fieldName>

<index> := '[' <indexValue> ']'If the variable is mapped using the SimpleMapper, the file names will consist

of some prefix followed by the relevant sequence of <fieldName> or

<indexValue> separated by some separator and ending with a suffix.

For example, given the following Swift code:

type person {

string name;

file address;

file data;

int age;

}

person[] employees <SimpleMapper; prefix = "employee", separator = "-",

suffix = ".txt">;the mapping would be:

| Leaf | File |

|---|---|

employees[1].address |

"employee-0001-address.txt" |

employees[1].data |

"employee-0001-data.txt" |

employees[2].address |

"employee-0002-address.txt" |

employees[2].data |

"employee-0002-data.txt" |

Parameters:

-

location -

Represents a directory where the files are located.

-

prefix -

If specified, prepends a prefix to all file names mapped by this mapper

-

suffix -

If specified, appends a suffix to all file names mapped by this mapper

-

pattern -

When used as an input mapper, this parameter represents an extended glob pattern that can be used to restrict the files mapped by this mapper. The extended glob pattern recognizes the following special symbols:

-

? -

Matches a single character

-

* -

Matches any number of arbitrary characters within a single path element (directory name or file name)

-

** -

Recursively matches all sub-directories

-

-

padding -

The minimum number of characters to use for integer indices. All index values whose string representation have fewer characters than the value of

paddingwill be zero-padded -

separator -

A string used to separate consecutive field names or index values

If the SimpleMapper is used to map arrays whose indices are not integers, an

unspecified string representation will be used for the portions of the file

names corresponding to the non-integer indices.

<FixedArrayMapper; string[] files>Maps an array of file-valued items and integer keys using a list of files. The

array must not be sparse and the first index is zero. Using the

FixedArrayMapper closes the array (but not its items) and fixes its length.

<FixedArrayMapper; string files>Similar to FixedArrayMapper above, except the files are specified as a

comma-separated list (with optional whitespace) of files. Example:

file[] texts <FixedArrayMapper; files = "file1.txt, fileB.txt, file3.txt">;

<FilesysMapper; string location = ".", string prefix = "", string suffix = "",

string pattern = "*">Maps an array of file-valued items and integer keys using a set of files

obtained from the filesystem. FilesysMapper searches for files in a location

based on a certain suffix, prefix and extended glob pattern an assigns the

resulting list of files to the array starting at index zero.

Parameters:

-

location -

Represents a directory where the files are located.

-

prefix -

If specified, only include files that have this prefix.

-

suffix -

If specified, only include files that have this suffix.

-

pattern -

An extended glob pattern used to filter the files. The extended glob pattern recognizes the following special symbols:

-

? -

Matches a single character

-

* -

Matches any number of arbitrary characters within a single path element (directory name or file name)

-

** -

Recursively matches all sub-directories

-

<RegexpMapper; string source, string match, string transform>Uses a regular expression substitution to create a mapping from an existing one.

The value of source is transformed using the regular expression substitution

and the result is used to map a single file value.

Parameters:

-

source -

A string (presumably representing an existing path)

-

match -

A regular expression

-

transform -

A string that can contain references to capture groups in the regular expression specified using the

matchparameter. The capture group references are in the form\\[0-9]

Example:

file s <"picture.gif">;

file f <RegexpMapper; source = filename(s), match="(.*)gif",

transform="\\1jpg">;

<StructuredRegexpMapper; any source, string match, string transform>An extension of RegexpMapper that can be used for

both single file values and complex types.

Parameters:

-

source -

Can either be a

string, in which caseStructuredRegexpMapperwill behave as a RegexpMapper, or a an array with items being either strings or file valued types, in which caseStructuredRegexpMapperwill apply the regular expression substitution to every item or the corresponding path that the item is mapped to. -

match -

A regular expression

-

transform -

A string that can contain references to capture groups in the regular expression specified using the

matchparameter. The capture group references are in the form\\[0-9]

Example:

file[] a <SimpleMapper; location = ".", prefix = "img", suffix = ".gif">;

file[] b <StructuredRegexpMapper; source = a, match="(.*)gif",

transform="\\1jpg">;

<CSVMapper; any file, boolean header = true, int skip = 0, string hdelim = " \t,", string delim = " \t,">The CSVMapper allows mapping of arrays of structures according to a file

formatted using a custom CSV-like format. The lines in the file correspond

to items in the array (starting at index zero) and the columns corerspond

to structure fields. A header in the CSV file can be used to specify the

structure field names.

Parameters:

-

file -

Can be a

stringcontaining the path name of the CSV file or a file-value that maps to the CSV file from which the data is read. -

header -

If set to

true, it indicates that the first line in the CSV file contains the names of the structure fields that are being mapped. If set tofalse, theCSVMapperassumes that the structure fields are named"column1","column2", etc. -

skip -

A value indicating an amount of lines to skip in the beginning of the CSV file. If

headeris set totruethe lines are skipped after reading the header. -

hdelim -

A set of characters that delimit header coulmns. Any of the characters are considered delimiters and they can be mixed. For example, if

hdelimis set to",;", then both of the following headers are valid and yield the same result:"colname1,colname2,colname3","colname1;colname2,colname3". -

delim -

Like

hdelim, except it applies to data lines.

<ArrayMapper; file[] files>TODO: There seems to be no difference between this and FixedArrayMapper.

<Ext; string exec, *>The Ext+ernal mapper invokes a sub-process to obtain mappings for arbitrary

types. The output from the process must be formatted as field file name pairs separated by whitespace. The field is the qualifying part of an

lvalue with array keys restricted to +int, float or

string primitive literals. If there is no qualifying part, such as when

reading the mapping for a non-composite file type, the field must be

the dollar sign ($). The file names are strings without quotes.

Parameters:

-

exec -

A path to an executable that will print, on its standard output stream, the mappings according to the format specified above.

-

* -

Any other parameters to the

Extmapper will be passed to the mapping executable in the form-<parameterName> <value>.

Example:

file[] array <Ext; exec = "mapper.sh", suffix = ".txt">;#!/bin/bash

SUFFIX=

if [ "$1" == "-suffix" ]; then

SUFFIX=$2

else

echo "Invalid parameter: $1"

exit 1

fi

echo "[0] array-0000$SUFFIX"

echo "[1] array-0001$SUFFIX"

echo "[2] array-0002$SUFFIX"

<ConcurrentMapper; string prefix, string suffix, string pattern, string location>The concurrent mapper is an extension to the SimpleMapper that guarantees unique mappings for all variables declared in the same program, but does not specify exactly what the form of the mapping is.

3. The Swift Runtime

Swift is a deterministic dataflow language. The lexical ordering of statements is generally irrelevant. What is relevant are the dependencies between data.

3.1. Values as Futures

Each value in Swift is a future. A future wraps a concrete value and has two possible states:

- Open

-

(or unbound). This is the default initial state of a value. The concrete value is absent and cannot yet be used in a concrete operation. It will be available at a later time.

- Closed

-

(or bound). This is a state in which a concrete value is available and can be used in an operation.

If a value is open at some time, it can be closed only at a later time. It is not possible for a variable to become open after it was closed.

Value literals are represented with futures that are closed when a program starts execution.

3.2. Order of Operations

Independent operations in Swift are all executed in parallel. However, operations can depend on values which must be closed before the respective operations can be executed. Consider the following example:

int a = 1;

int b = 2;

int c = f(a) + g(b);The following operations can be identified:

-

three assignments, for variables

a,bandc -

two function invocations:

f(a)andg(b) -

an addition operation

All these operations are started in parallel as soon as Swift starts running the

program. The assignments to variables a and b can continue immediately since

they depend only on integer literals, which are closed by default. The

invocations of f and g can then continue. The addition has to wait for the

results from the invocations of both f and g. When those results are

available, the addition can be peformed and the resulting value can be finally

assigned to c.

3.3. Types of Operations

Technically speaking, many things can be considered “operations”. However, it is worth emphasizing some of them due to the particular way in which they are executed.

- Assignments

-

The assignment statement waits for the right hand side to be closed, copies the concrete value from the right hand side to the left hand side, and finally closes the left hand side.

|

|

See also: assignment of mapped values |

- Application Functions

-

An application instance will only run after all of its actual parameters are closed. After an application invocation completes, all the actual return parameters are closed by Swift.

- Function Invocations

-

When a non-application function is invoked, it does not necessarily wait for all of its actual parameters to be closed. The details depend on the actual definition of the function. Consider the following example:

(int result) product(int f1, int f2) { if (f1 == 0) { result = 0; } else { result = f1 * f2; } } int r1 = product(0, x); int r2 = product(2, x);Two cases exist:

-

In the first invocation of the

productfunction, the parameterf1is zero. The first branch of theifcondition is taken, which does not include an operation that waits for the value off2to be closed. -

In the second invocation, the value of

f1is non-zero. The second branch of theifis taken. This branch contains an operator that has the values of bothf1andf2as parameters. In this case theproductfunction needs to wait forf2to be closed before producing a result.

For functions defined in the Swift standard library, it is implied that the implementation will always wait for the value of the parameters to be closed. Any exceptions to this rule are explicitly documented.

-

- Operators

-

There is no semantic difference between operator invocations and library function invocations, so the above rule applies. In particular, the current implementation does not implement shortcut evaluation for boolean operators.

3.4. Arrays and Iterations

Arrays in Swift are sparse. This means that array sizes, in general, can only be fully determined at run-time. Because of this, the array structure itself has the properties of a future. Consider the following example:

int[] a, b;

a[0] = 1;

iterate i {

int value = someComplexFunction(i);

a[i + 1] = value;

} until (value > 100);

foreach x, i in a {

b[i] = f(x);

}Since iterate and foreach run in parallel, the foreach will start before

a is fully constructed. We assume that the iterate condition

eventually becomes true. In order for the program to terminate and

function deterministically, the foreach must eventually terminate and it must

not do so before all the items have been added to a. Arrays must therefore

have two states:

- Open array

-

In this state it is unknown whether more items will be added to an array or not.

- Closed array

-

Both the size of the array and the indices corresponding to all the items in the array are known.

A foreach statement will start, in parallel, an iteration for each item

available in an array. As more items are added to the array, foreach will

start the corresponding iterations. When the array becomes closed and all

iterations complete, foreach will complete.

3.4.1. When are Arrays Closed

The determination of when an array can be closed is made based on analyzing all

source code locations in which that array is written to. In the last example

above, all writing operations to a are done within the iterate statement.

The Swift compiler will generate code to close a as soon as the iterate

statement completes.

3.4.2. Writing to an Array that is Being Iterated on

Swift allows writing to an array that is being iterated on using the foreach

statement:

int[] a;

a[0] = 1;

foreach x, i in a {

int value = someComplexFunction(i);

if (value <= 100) {

a[i + 1] = value;

}

}Swift handles array closing slightly differently in the case of

“self referencing” foreach statements. The a array will be closed when

both the following conditions are true:

-

All writing operations to

aoutside of theforeachhave completed -

Iterations for all available items in

ahave completed

This can be used to implement everything that can be implemented using the

iterate statement, possibly in a more clear fashion. Users are encouraged

to use foreach instead of iterate.

3.5. Circular Dependencies

Circular dependencies are situations in which two or more values form a dependency cycle through operations applied on them. The simplest case is that of two mutually dependent values:

int a, b;

a = f(b);

b = f(a);The variable a cannot be closed until b is closed which in turn cannot be

closed until a is closed. Situations like this will cause a Swift program

to stop progressing. This is detected by the Swift run-time and results in a

run-time error.

While the above situation can theoretically be detected at compile-time, this cannot be done in all cases. Consider the following example:

int[] a;

a[0] = 1;

a[1] = a[getIndex(1)];

a[2] = a[getIndex(2)];It is possible, but not necessary, that at run-time the above code will result in:

int[] a;

a[0] = 1;

a[1] = a[2];

a[2] = a[1];This can only be determined by knowing the values returned by the

getIndex() function, which in general can only be done at run-time.

3.6. Error Handling

TODO

3.7. File Mapping

File mapping is the process through which values stored in Swift variables of mapped types are associated with physical files. This process is implemented by mappers which are specified using mapping declarations. A non-composite mapped value can be associated to a file using the SingleFileMapper or its short form:

file f <"file.dat">;The above code associates the variable f to a local file named file.dat

which is assumed to be in the directory from which Swift is invoked. It is

possible to more complex path names or even URLs to associate a Swift variable

with files that do not necessarily reside in the current directory:

file f1 <"/tmp/file.dat">;

file f2 <"http://example.org/index.html">;For a list of all supported remote file access methods, please see Filesystem Providers.

Values of composite types containing file-valued data can be mapped in bulk using one of the additional mappers provided by Swift. For example, the FilesysMapper can be used to glob files in a directory and map them to an entire array:

file[] a <FilesysMapper; location = ".", pattern = "*.dat">;3.7.1. Implicit Mapping

A mapped type value that is not mapped explicitly is implicitly mapped. Specifically Swift will map it to a deterministic but opaque temporary file.

3.7.2. Input or Output

Swift distinguishes between input and output mapped data based on whether explicit assignments are present in the program. If a variable is assigned to in a Swift program, Swift considers that variable to be an output. Otherwise, Swift marks it as an input. When a variable is marked as an input, Swift requires that the corresponding files be present, unless the variable is an array that can be empty. An input mapped variable is considered to be implicitly assigned. Example:

file f <"input.dat">;  file g <"output.dat">;

file g <"output.dat">;  g = cat(f);

g = cat(f);

Variable f is not explicitly assigned to. It is therefore an input

variable, and Swift implicitly assigns a file value representing the input.dat

file to it. It is an error for input.dat not to exist as a file.

| |

Variable g is explicitly assigned to. It is therefore an output and it

will be created by Swift during the program’s execution.

|

It does not make sense for certain mappers to be used for output (such as the FilesysMapper), since their operation depends on having a set of physical files present.

3.7.3. Assignment of Mapped Values

When a mapped value is assigned to a mapped type variable, and the destination variable is not implicitly mapped, Swift guarantees that the file that the destination variable is mapped to will exist. This is generally done by copying the file. However, Swift may optimize this when possible, in particular by creating symbolic links on systems that support it.

3.8. Application Functions Execution

Applications in Swift are generally executed on remote computing resources. In the Swift language, applications functions are specified in a way that is independent of where and how applications are run, which allows application instances to be scheduled efficiently based on resource availability. When an application function is invoked, the following steps are taken:

-

Swift waits for all the actual parameters to the application function to be closed

-

Site selection: a remote resource is selected from all available resources based on whether they contain the given application, load, and other run-time information (see Section on Site Selection).

-

A file sandbox is created, where the application input and output files will be stored

-

All files corresponding to mapped values in the actual parameters are copied to the application sandbox ("stage-in")

-

The application is executed remotely using one of the available execution mechanisms

-

All files corresponding to mapped values in the actual return parameters are copied back from the application sandbox, and the actual return parameters are closed ("stage-out")

-

The application sandbox is deleted

The application execution is performed indirectly. A small script, called

"wrapper" (or _swiftwrap), is used to implement the following functions:

-

set up the details of the application sandbox, such as directory structures where input and output files go

-

perform basic tests of the environment and try to generate user-friendly error messages if something is wrong

-

copy or link files from a resource-local swift cache to the application sandbox and back

-

optionally clean up the application sandbox

-

record the status of the application execution

-

log various application timing information

There are three ways in which the above operations can be performed and they will be explained in detail in the following sections: swift staging, provider staging, and wrapper staging.

3.8.1. Swift Staging

Swift staging is historically the first mechanism used by Swift to deal with

remote application files. In swift staging mode (selected through the

staging: "swift" configuration option), for each

job, the Swift runtime selects a site as described in

Site Selection, and, using that site, it performs

the following operations in order:

-

Using the filesystem provider specified in the configuration file, it creates a shared directory in the location specified by the

workDirectorysite property that will mirror the local directory structure with respect to all files used by applications running on that site. This directory is only created once per site per swift program execution, and it is initially empty. It is guaranteed that two invocations of swift programs will have different shared directories on a given site. -

In the shared directory, Swift creates the directory structure needed by the job’s input and output files. For example, if an application uses the following input:

file f <"data/f.dat">;then Swift will create a directory named

datainside the site shared directory. -

Using the filesystem provider, swift copies all the application’s input files into their respective directories inside the shared directory. Files that are already in the shared directory are skipped.

-

The application is invoked through

_swiftwrap. The essential steps taken by_swiftwrapin Swift staging mode are as follows:-

Create a sandbox directory either inside the shared directory, or in a temporary location if the

scratchproperty is specified for the site -

For each of the application’s input files, either copy the file from the shared directory into the sandbox directory or create a symbolic link inside the sandbox directory to the file in the shared directory. The choice of whether to copy or link is determined by existence of the

scratchproperty. If the property is defined for the site, then the files will be copied. The copying process preserves the directory structure. -

Run the application

-

If the application returns a zero exit code indicating success, then:

-

Check that all the output files were created by the application and fail if not

-

Move the output files from the sandbox directory back to the shared directory preserving the directory structure

-

Remove the job directory

-

-

Exit signalling success or failure; the exact method of signalling depends on the value of the

statusModeproperty. If set toprovider, then_swiftwrapexits with an exit code equal to the exit code of the application. If set tofiles, then swift creates either an empty success file or a failure file containing the application exit code

-

-

Transfer and check the status files for the job status if

statusModeisfiles -

Copy all application output files back to the machine that Swift is running on

For example, consider the following Swift program:

app (file outf) cat(file inf) {

"/bin/cat" filename(inf) stdout = filename(outf);

}

file inf <"inputs/a.dat">;

file outf <"outputs/b.dat">;

outf = cat(inf);and the following configuration:

site.cluster {

execution {

type: "GRAM"

url: "login.cluster.example.org"

jobManager: "PBS"

}

filesystem {

type: "GSIFTP"

url: "login.cluster.example.org"

}

statusMode: "provider"

staging: "swift"

workDirectory: "/homes/johndoe/swiftwork"

}

sites: [cluster]Swift would execute the cat application as follows:

A few observations are in order:

-

statusMode: "files"was historically used to deal with execution providers that did not have a mechanism of reporting the application exit code. The most notable example is the early implementation of the GRAM protocol from the Globus Toolkit version 2. It is unlikely to be needed. -

when running on compute clusters, the shared directory and therefore the work directory needs to reside on a shared filesystem that is accessible from the compute nodes.

-

transfers and other file operations are all controlled directly by Swift and are governed by throttling settings, such as

fileTransfersThrottleandfileOperationsThrottle. Throttling limits the number of concurrent operations and is useful to increase stability without affecting performance. -

use of a

scratchoption pointing to a compute-node local filesystem can yield better performance if the work directory resides on a shared filesystem that has high latencies and high throughput. The performance improvement also depends on how the application accesses its input files and is more noticeable if the application uses a random-access pattern on its input files rather than sequential reads. -

while Swift staging is mostly superseded by provider staging through Coasters, there are still legitimate reasons to use Swift staging, such as running MPI applications through GRAM and a local resource manager (e.g. PBS).

3.8.2. Provider Staging

With provider staging, Swift delegates the task of transferring files to the compute nodes to the execution provider. The full functionality needed to manage all the file operations needed by a job are currently only supported by the Coasters execution provider, so provider staging requires the use of Coasters.

Since the provider takes care of shipping files to the compute nodes, there is no strict need for a shared filesystem on the cluster except as needed by Coasters. Files on the Swift side, as well as the job sandboxes, can reside on directly-attached disks. This can improve performance with respect to shared filesystems that would have non-trivial latencies.

Wrapper staging is enabled by specifying one of local, service-local,

shared-fs or direct choices to the staging

site configuration property. The meaning of the various choices is as follows:

-

local -

files are assumed to reside on the machine where Swift is running. Coasters will copy the files using the Coaster Service as a proxy. This allows files to be copied even if the compute nodes cannot reach networks outside of the cluster they belong to.

-

service-local -

files are assumed to reside on the machine where Swift is running and the Coaster Service is assumed to be running on the same machine.

-

shared-fs -

files are assumed to reside on a shared filesystem that is accessible by the compute nodes and are copied using standard POSIX copying routines.

-

direct -

this is an experimental mode similar to

shared-fsin which no copying to a sandbox is actually done. Instead, applications are passed the absolute paths to the files involved.

Using the same example application as in the case of Swift staging, an example

set of operations performed by Swift with staging: local is shown below:

3.8.3. Wrapper Staging

Wrapper staging is an experimental feature that allows _swiftwrap to perform

the necessary file staging operations. It generally requires a shared

filesystem accessible from the compute nodes.

3.9. Data flow and staging

3.9.1. Overview

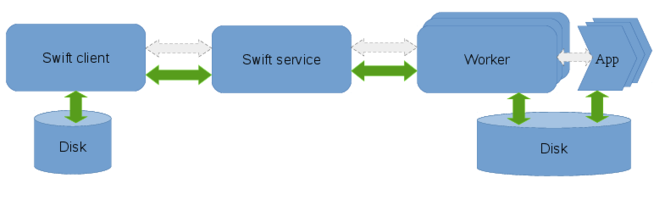

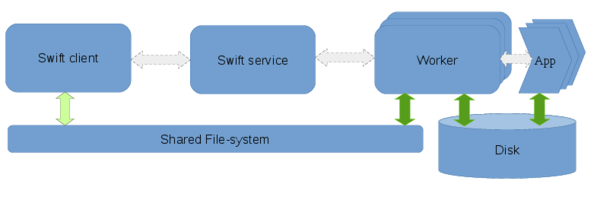

The execution components involved in a Swift workflow are the client, the swift service and the workers. The client is the program that executes the workflow described in a swift script and is invoked by the swift command. The service may be started separately or automatically by the swift client and is responsible for provisioning resources from clouds, clusters or HPC systems. The workers are launched by the swift-service and are responsible for controlling the execution of the user’s application on the compute nodes.

Different clusters, HPC systems, and cloud vendors may have shared file-systems, varying network characteristics and local-disks available which can be utilized differently to marshal data efficiently within a workflow. Data flow refers to this movement of data within a workflow. On distributed systems with varying levels of shared resources, the Swift client and service coordinates the flow of data among the worker-nodes such that the data required for computation is available to the worker prior to the execution of the users’s application as well as ensuring that the computed results are captured once tasks run to completion.

There are 6 different staging methods that are supported by Swift. They are:

-

Local

-

Direct

-

Wrapper

-

Swift

-

Shared-fs

-

Service-local

These staging methods are explained in detail in the following sections.

Legend for the following sections:

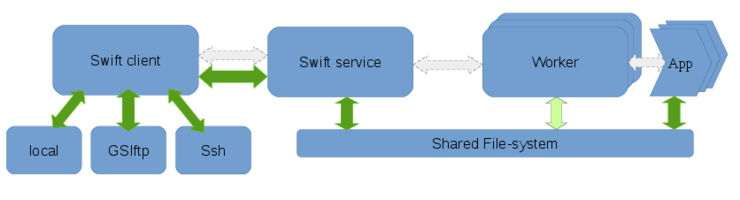

3.9.2. Staging method : local

Data flow in local staging:

Summary

The local staging method is designed for shared-nothing architectures such as clusters and clouds with no shared file-systems. The data originates on the node where the client runs and all data transfers are done explicity over the network. This method avoids using a shared-filesystem to transfer the files over the network, as in many cases the shared-filesystem is a shared among multiple users which adds congestion and it also could just be unsuitable for certain file access patterns. The client and service need not be on the same machine, which allows a client running on a local workstation to channel data through a service on the headnode of a Cluster1 to compute nodes provisioned from Cluster1. The is the default file staging method as this works on all computational resources. Since all the data is transferred via the swift-service the network bandwidth of the service could bottleneck the data flow. Similarly if the swift client is running remotely, the network links between the client and the service could potentially become a bottleneck for large volumes of data.

When to use this mode

The data volumes that need to be transferred to and from the workers to the client per worker are not more that hundreds of MB. As data sizes approach GBs of data per task, other transport mechanisms such as Globus transfers are worth considering.

When each task either consumes or generates a large number of small files, shared-filesystem based copies can be very slow. The local staging method is an ideal candidate for this scenario. However, when there are large number of files involved the filesystem of the system on which the client is executing could become a bottleneck. Using a faster non-disk filesystem when available generally improves performance significantly.

Example configs

sites: midway

site.midway {

execution {

type: "coaster"

URL: "swift.rcc.uchicago.edu"

jobManager: "ssh-cl:slurm" # Client connects remotely to the login node.

options {

nodeGranularity: 1

maxNodesPerJob: 1

jobQueue: "sandyb"

maxJobs: 1

tasksPerNode: 1

maxJobTime: "00:08:20"

}

}

staging: "local"

workDirectory: "/tmp/"${env.USER}

app.date {

executable: "/bin/date"

maxWallTime: "00:05:00"

}

}Performance

All data-flow is over the network links from the client node and service node in this staging method and as a result, the network capacity of the client node is a potential limiting factor for large data volumes.

When several small files are involved, or with sufficiently large files, the filesystem on the client node can become a bottleneck.

There are performance limitations to the the staging/transport mechanism that swift uses, which could limit transfer throughputs. [TODO: Data to support this would be very nice]

Notes:

When running using local coasters (local instead of ssh-cl), the client and service run on the same node. In this case, the network links are between the service and workers.

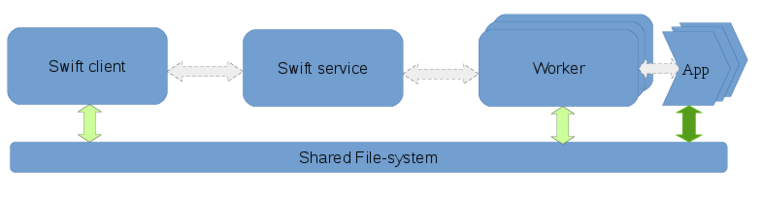

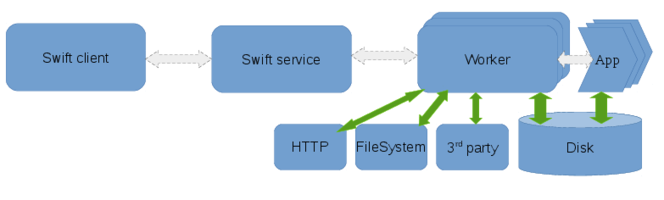

3.9.3. Staging method : Direct

Data flow with Direct staging:

Data flow with Direct staging and a scratch directory:

Summary

The direct staging mode is designed for computational resources with High-Performance shared-filesystems. This mode requires that a shared filesystem such as NFS, Lustre, or even FUSE-mounted-S3 is mounted across the nodes where the client, service, and the workers are executing. Instead of Swift managing network transfers, the network transfers are implicitly managed by the shared-filesystem. The apps run in sandbox directories created under the workDirectory, but the tasks themselves will receive absolute paths for the input and output files. For applications that are IO bound, writing directly to the shared-filesystem can adversely affect the shared filesystem performance. To avoid this there is an option to specify a “scratch” folder on a local disk on the compute nodes.

When to use this mode

Large volumes of data are either consumed or generated by the application and a High Performance shared-filesystem is available across the nodes. On systems which have shared-filesystems, with I/O bandwidth that exceeds the network links between the headnode and the worker nodes, using the network to transfer data to the compute nodes could be sub-optimal.

When a high-performance shared filesystem is available, such as the case on many supercomputing systems, there is sufficient I/O bandwidth to support several applications reading and writing to the filesystem in parallel.

Another scenario is when the shared-filesystem is sensitive to creation and deletion of small files and directories. The swift workers create a sandbox directory for each task, which is (3 : TODO:confirm this with Mihael) levels deep. Using the direct mode with the workDirectory on a local disk (say /tmp) could avoid the overhead from swift’s mechanisms for sandboxing tasks.

Example configs

The following is an example for the direct staging mode. * Staging method is set to “direct”. * workDirectory may be set to the shared filesystem or a local filesystem.

In this case, Swift assumes that file variables point at files on the shared filesystem. The apps which are executed on the workers resolve the file variables to absolute paths to the input and output files on the shared-filesystem.

sites: midway

site.midway {

execution {

type: "coaster"

URL: "swift.rcc.uchicago.edu"

jobManager: "local:slurm"

options {

nodeGranularity: 1

maxNodesPerJob: 1

jobQueue: "sandyb"

maxJobs: 1

tasksPerNode: 1

maxJobTime: "00:08:20"

}

}

staging: direct

workDirectory: "/tmp/"${env.USER}"/swiftwork"

app.bash {

executable: "/bin/bash"

maxWallTime: "00:05:00"

}

}The following is an example for the direct staging mode.

-

Staging method is set to “direct”

-

workDirectory may be set to the shared filesystem or a local filesystem.

-

Scratch is set to a directory on the local disks of the workers.

Since the staging method is set to “direct”, swift will assume that file are on a shared file-system. In the context of user-application the file variables will resolve to absolute paths of the input/output files on the scratch directory. Before the workers start the execution of user tasks, the workers will copy the input files from the shared-filesystem to the scratch directory, and after execution will copy out the output files from the scratch directory to the shared-filesystem.

sites: midway

site.midway {

execution {

type: "coaster"

URL: "swift.rcc.uchicago.edu"

jobManager: "local:slurm"

options {

nodeGranularity: 1

maxNodesPerJob: 1

jobQueue: "sandyb"

maxJobs: 1

tasksPerNode: 1

maxJobTime: "00:08:20"

}

}

staging: direct

workDirectory: "/tmp/"${env.USER}"/swiftwork"

scratch: "/scratch/local/"${env.USER}"/work/"

app.bash {

executable: "/bin/bash"

maxWallTime: "00:05:00"

}

}

TCPPortRange: "50000,51000"

lazyErrors: false

executionRetries: 0

keepSiteDir: true

providerStagingPinSwiftFiles: false

alwaysTransferWrapperLog: trueNotes:

TODO : Details of the filename behavior in apps and within swiftscript body.

When this configuration is used, the worker copies the input files from the shared-filesystem to the scratch directory, and the user application will get the path to the file on scratch when the filename(<file_variable>) and it’s shorthand @<file_variable> primitives are used in the app definition. The filename and @ primitives when used outside of the app definitions will point at the files on the shared-filesystem.

Performance

"Direct" is theoretically the optimal way to use the shared-filesystem. There are no unnecessary copies, and the application that requires the file alone access the data.

If the data access pattern of the application involves random seeks or creation of several intermediate small files, the "scratch" option allows you to offload sub-optimal file access patterns to a local disk/memory. This avoids costly accesses on the shared-filesystem and indirectly the network.

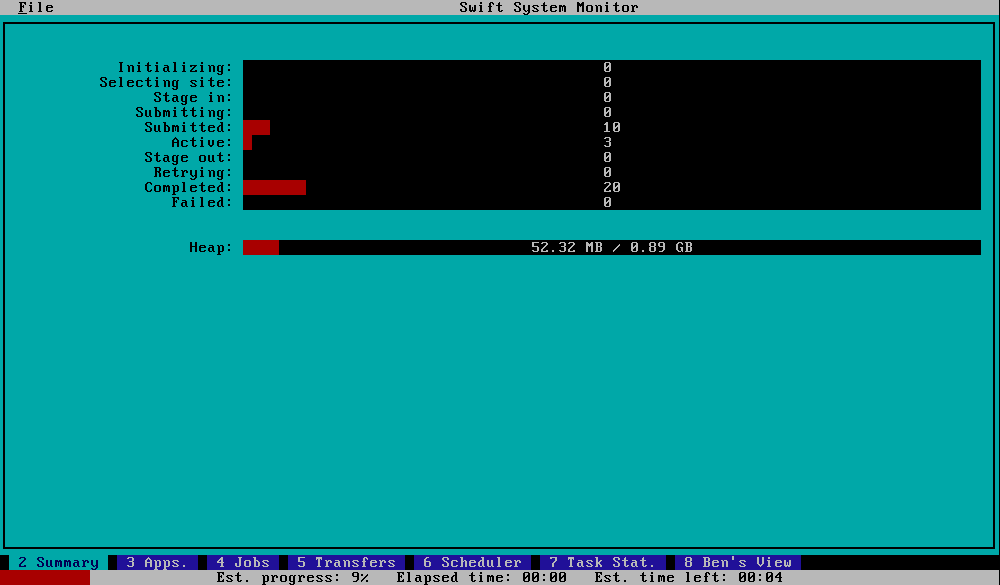

3.9.4. Staging method : Swift

Data flow with staging method Swift:

Summary

Swift staging, involves the client accessing file over a supported method like ssh or a local-filesystem access, and making the inputs available to the workers over a work-directory on a shared filesystem. This staging method uses an intermediate staging location that is on a shared-FS so each files is, in addition to being read from the initial location, written to and read from a shared FS, both of each are overhead. The only advantage to this is that you don’t need coasters to use it and it’s supported on a large number of computational resources.

This is the default staging mechanism used if no staging method is defined in the swift config file.

When to use this mode

-

You can access data using one of the supported methods like: local filesystem access ssh - Use scp to access files GSIFTP GridFTP

-

A shared-FS is present, that works well for your data access patterns.

-

You want to use a non-coaster execution provider.