This tutorial is viewable at: http://swiftlang.org/tutorials/midway/tutorial.html

Introduction: Why Parallel Scripting?

Swift is a simple scripting language for executing many instances of ordinary application programs on distributed parallel resources. Swift scripts run many copies of ordinary programs concurrently, using statements like this:

foreach protein in proteinList {

runBLAST(protein);

}Swift acts like a structured "shell" language. It runs programs concurrently as soon as their inputs are available, reducing the need for complex parallel programming. Swift expresses your workflow in a portable fashion: The same script runs on multicore computers, clusters, clouds, grids, and supercomputers.

In this tutorial, you’ll be able to first try a few Swift examples (parts 1-3) on a Midway login host, to get a sense of the language. Then in parts 4-6 you’ll run similar workflows on Midway compute nodes, and see how more complex workflows can be expressed with Swift scripts.

Swift tutorial setup

If you are using a temporary/guest account to access Midway, follow the instructions at http://docs.rcc.uchicago.edu/tutorials/intro-to-rcc-workshop.html for more information on using a yubikey to log in.

Once you are logged into the Midway login host, run the following commands to set up your environment.

$ cd $HOME

$ wget http://swiftlang.org/tutorials/midway/swift-midway-tutorial.tar.gz

$ tar xvfz swift-midway-tutorial.tar.gz

$ cd swift-midway-tutorial

$ source setup.shVerify your environment

To verify that Swift loaded, do:

$ swift -version # verify that you have Swift 0.95 RC1|

|

If you re-login or open new ssh sessions, you must re-run source setup.sh in each ssh shell/window. |

To check out the tutorial scripts from SVN

If you later want to get the most recent version of this tutorial from the Swift Subversion repository, do:

$ svn co https://svn.ci.uchicago.edu/svn/vdl2/SwiftTutorials/swift-midway-tutorialThis will create a directory called "swift-midway-tutorial" which contains all of the files used in this tutorial.

Simple "science applications" for the workflow tutorial

This tutorial is based on two intentionally trivial example programs,

simulation and stats, (implemented as bash shell scripts)

that serve as easy-to-understand proxies for real science

applications. These "programs" behave as follows.

simulate.sh

The simulation script serves as a trivial proxy for any more complex scientific simulation application. It generates and prints a set of one or more random integers in the range [0-2^62) as controlled by its command line arguments, which are:

$ simulate -help

simulate: usage:

-b|--bias offset bias: add this integer to all results

-B|--biasfile file of integer biases to add to results

-l|--log generate a log in stderr if not null

-n|--nvalues print this many values per simulation

-r|--range range (limit) of generated results

-s|--seed use this integer [0..32767] as a seed

-S|--seedfile use this file (containing integer seeds [0..32767]) one per line

-t|--timesteps number of simulated "timesteps" in seconds (determines runtime)

-x|--scale scale the results by this integer

-h|-?|?|--help print this helpAll of these arguments are optional, with default values indicated above as [n].

With no arguments, simulate prints 1 number in the range of 1-100. Otherwise it generates n numbers of the form (R*scale)+bias where R is a random integer. By default it logs information about its execution environment to stderr. Here’s some examples of its usage:

$ simulate 2>log

51

$ head -5 log

Called as: /home/davidkelly999/swift-midway-tutorial/app/simulate:

Start time: Mon Dec 2 13:47:41 CST 2013

Running as user: uid=88848(davidkelly999) gid=88848(davidkelly999) groups=88848(davidkelly999),10008(rcc),10030(pi-gavoth),10031(sp-swift),10036(swift),10058(pi-joshuaelliott),10084(pi-wilde),10118(cron-account),10124(cmts),10138(cmtsworkshop)

$ simulate -n 4 -r 1000000 2>log

239454

386702

13849

873526

$ simulate -n 3 -r 1000000 -x 100 2>log

6643700

62182300

5230600

$ simulate -n 2 -r 1000 -x 1000 2>log

565000

636000

$ time simulate -n 2 -r 1000 -x 1000 -t 3 2>log

336000

320000

real 0m3.012s

user 0m0.005s

sys 0m0.006sstats

The stats script serves as a trivial model of an "analysis" program. It reads N files each containing M integers and simply prints the average of all those numbers to stdout. Similarly to simulate it logs environmental information to the stderr.

$ ls f*

f1 f2 f3 f4

$ cat f*

25

60

40

75

$ stats f* 2>log

50Basic of the Swift language with local execution

A Summary of Swift in a nutshell

-

Swift scripts are text files ending in

.swiftTheswiftcommand runs on any host, and executes these scripts.swiftis a Java application, which you can install almost anywhere. On Linux, just unpack the distributiontarfile and add itsbin/directory to yourPATH. -

Swift scripts run ordinary applications, just like shell scripts do. Swift makes it easy to run these applications on parallel and remote computers (from laptops to supercomputers). If you can

sshto the system, Swift can likely run applications there. -

The details of where to run applications and how to get files back and forth are described in configuration files separate from your program. Swift speaks ssh, PBS, Condor, SLURM, LSF, SGE, Cobalt, and Globus to run applications, and scp, http, ftp, and GridFTP to move data.

-

The Swift language has 5 main data types:

boolean,int,string,float, andfile. Collections of these are dynamic, sparse arrays of arbitrary dimension and structures of scalars and/or arrays defined by thetypedeclaration. -

Swift file variables are "mapped" to external files. Swift sends files to and from remote systems for you automatically.

-

Swift variables are "single assignment": once you set them you can’t change them (in a given block of code). This makes Swift a natural, "parallel data flow" language. This programming model keeps your workflow scripts simple and easy to write and understand.

-

Swift lets you define functions to "wrap" application programs, and to cleanly structure more complex scripts. Swift

appfunctions take files and parameters as inputs and return files as outputs. -

A compact set of built-in functions for string and file manipulation, type conversions, high level IO, etc. is provided. Swift’s equivalent of

printf()istracef(), with limited and slightly different format codes. -

Swift’s

foreach {}statement is the main parallel workhorse of the language, and executes all iterations of the loop concurrently. The actual number of parallel tasks executed is based on available resources and settable "throttles". -

In fact, Swift conceptually executes all the statements, expressions and function calls in your program in parallel, based on data flow. These are similarly throttled based on available resources and settings.

-

Swift also has

ifandswitchstatements for conditional execution. These are seldom needed in simple workflows but they enable very dynamic workflow patterns to be specified.

We’ll see many of these points in action in the examples below. Lets get started!

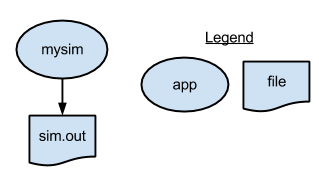

Part 1: Run a single application under Swift

The first swift script, p1.swift, runs simulate to generate a single random number. It writes the number to a file.

type file;

app (file o) simulation ()

{

simulate stdout=filename(o);

}

file f <"sim.out">;

f = simulation();To run this script, run the following command:

$ cd part01

$ swift p1.swift

Swift 0.94.1 RC2 swift-r6895 cog-r3765

RunID: 20130827-1413-oa6fdib2

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:13:33 -0500

Final status: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:13:33 -0500 Finished successfully:1

$ cat sim.out

84

$ swift p1.swift

$ cat sim.out

36To cleanup the directory and remove all outputs (including the log files and directories that Swift generates), run the cleanup script which is located in the tutorial PATH:

$ cleanup|

|

You’ll also find a Swift configuration file in each partNN

directory of this tutorial. This file specifies the environment-specific

details of how to run. These files will be explained in more

detail in parts 4-6, and can be ignored for now. |

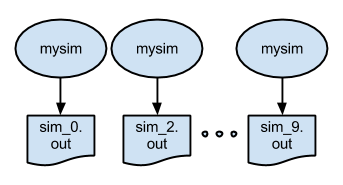

Part 2: Running an ensemble of many apps in parallel with a "foreach" loop

The p2.swift script introduces the foreach parallel iteration

construct to run many concurrent simulations.

type file;

app (file o) simulation ()

{

simulate stdout=filename(o);

}

foreach i in [0:9] {

file f <single_file_mapper; file=strcat("output/sim_",i,".out")>;

f = simulation();

}The script also shows an

example of naming the output files of an ensemble run. In this case, the output files will be named

output/sim_N.out.

To run the script and view the output:

$ cd ../part02

$ swift p2.swift

$ ls output

sim_0.out sim_1.out sim_2.out sim_3.out sim_4.out sim_5.out sim_6.out sim_7.out sim_8.out sim_9.out

$ more output/*

::::::::::::::

output/sim_0.out

::::::::::::::

44

::::::::::::::

output/sim_1.out

::::::::::::::

55

...

::::::::::::::

output/sim_9.out

::::::::::::::

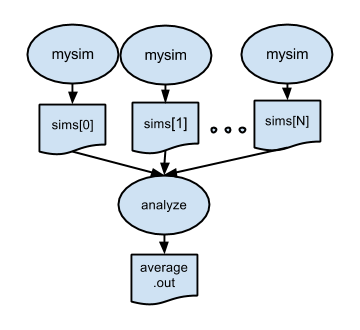

82Part 3: Analyzing results of a parallel ensemble

After all the parallel simulations in an ensemble run have completed,

its typically necessary to gather and analyze their results with some

kind of post-processing analysis program or script. p3.swift

introduces such a postprocessing step. In this case, the files created

by all of the parallel runs of simulation will be averaged by by

the trivial "analysis application" stats:

type file;

app (file o) simulation (int sim_steps, int sim_range, int sim_values)

{

simulate "--timesteps" sim_steps "--range" sim_range "--nvalues" sim_values stdout=filename(o);

}

app (file o) analyze (file s[])

{

stats filenames(s) stdout=filename(o);

}

int nsim = toInt(arg("nsim","10"));

int steps = toInt(arg("steps","1"));

int range = toInt(arg("range","100"));

int values = toInt(arg("values","5"));

file sims[];

foreach i in [0:nsim-1] {

file simout <single_file_mapper; file=strcat("output/sim_",i,".out")>;

simout = simulation(steps,range,values);

sims[i] = simout;

}

file stats<"output/average.out">;

stats = analyze(sims);To run:

$ cd part03

$ swift p3.swiftNote that in p3.swift we expose more of the capabilities of the

simulate application to the simulation() app function:

app (file o) simulation (int sim_steps, int sim_range, int sim_values)

{

simulate "--timesteps" sim_steps "--range" sim_range "--nvalues" sim_values stdout=@filename(o);

}p3.swift also shows how to fetch application-specific values from

the swift command line in a Swift script using arg() which

accepts a keyword-style argument and its default value:

int nsim = toInt(arg("nsim","10"));

int steps = toInt(arg("steps","1"));

int range = toInt(arg("range","100"));

int values = toInt(arg("values","5"));Now we can specify that more runs should be performed and that each should run

for more timesteps, and produce more that one value each, within a specified range,

using command line arguments placed after the Swift script name in the form -parameterName=value:

$ swift p3.swift -nsim=3 -steps=10 -values=4 -range=1000000

Swift 0.94.1 RC2 swift-r6895 cog-r3765

RunID: 20130827-1439-s3vvo809

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:39:42 -0500

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:39:53 -0500 Active:2 Stage out:1

Final status: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:39:53 -0500 Finished successfully:4

$ ls output/

average.out sim_0.out sim_1.out sim_2.out

$ more output/*

::::::::::::::

output/average.out

::::::::::::::

651368

::::::::::::::

output/sim_0.out

::::::::::::::

735700

886206

997391

982970

::::::::::::::

output/sim_1.out

::::::::::::::

260071

264195

869198

933537

::::::::::::::

output/sim_2.out

::::::::::::::

201806

213540

527576

944233Now try running (-nsim=) 100 simulations of (-steps=) 1 second each:

$ swift p3.swift -nsim=100 -steps=1

Swift 0.94.1 RC2 swift-r6895 cog-r3765

RunID: 20130827-1444-rq809ts6

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:44:55 -0500

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:44:56 -0500 Selecting site:79 Active:20 Stage out:1

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:44:58 -0500 Selecting site:58 Active:20 Stage out:1 Finished successfully:21

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:44:59 -0500 Selecting site:37 Active:20 Stage out:1 Finished successfully:42

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:45:00 -0500 Selecting site:16 Active:20 Stage out:1 Finished successfully:63

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:45:02 -0500 Active:15 Stage out:1 Finished successfully:84

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:45:03 -0500 Finished successfully:101

Final status: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 14:45:03 -0500 Finished successfully:101We can see from Swift’s "progress" status that the tutorial’s default parameters for local execution allow Swift to run up to 20 application invocations concurrently on the login node. We’ll look at this in more detail in the next sections where we execute applications on the site’s compute nodes.

Running applications on Midway compute nodes with Swift

Part 4: Running a parallel ensemble on Midway compute nodes

p4.swift will run our mock "simulation" applications on Midway

compute nodes. The script is similar to as p3.swift, but specifies

that each simulation app invocation should additionally return the

log file which the application writes to stderr.

Now when you run swift p4.swift you’ll see that two types output

files will placed in the output/ directory: sim_N.out and

sim_N.log. The log files provide data on the runtime environment of

each app invocation. For example:

$ cat output/sim_0.log

Called as: /home/davidkelly999/swift-midway-tutorial/app/simulate: --timesteps 1 --range 100 --nvalues 5

Start time: Mon Dec 2 12:17:06 CST 2013

Running as user: uid=88848(davidkelly999) gid=88848(davidkelly999) groups=88848(davidkelly999),10008(rcc),10030(pi-gavoth),10031(sp-swift),10036(swift),10058(pi-joshuaelliott),10084(pi-wilde),10118(cron-account),10124(cmts),10138(cmtsworkshop)

Running on node: midway002

Node IP address: 10.50.181.2 172.25.181.2

Simulation parameters:

bias=0

biasfile=none

initseed=none

log=yes

paramfile=none

range=100

scale=1

seedfile=none

timesteps=1

output width=8

Environment:

ANTLR_ROOT=/software/antlr-2.7-el6-x86_64

ANT_HOME=/software/ant-1.8.4-all

ANT_HOME_modshare=/software/ant-1.8.4-all:3

...Swift’s swift.properties configuration file allows many parameters to

specify how jobs should be run on a given cluster.

Consider for example that Midway has several Slurm partitions. The sandyb partition has 16 cores, and the westmere partition has 12 cores. Depending on the application and which partitions are busy, you may want to modify where you run.

Here is an example of the swift.properties in the part04 directory:

site=westmere

site.westmere.slurm.reservation=workshop

site.westmere.slurm.exclusive=falseThe first line, site=westmere, allows you to define which partition to run on. Swift includes templates for each partition that provides some reasonable default values. Other valid partitions are amd, bigmem, gpu, local, and sandyb.

The second and third line override some of the default values, by specifying a reservation that will be used for this session, and enabling node sharing.

Try changing the queue to run on the sandyb queue. The new swift.properties should look like this:

site=sandyb

site.sandyb.slurm.reservation=workshop

site.sandyb.slurm.exclusive=falsePerforming larger Swift runs

To test with larger runs, there are two changes that are required. The first is a change to the command line arguments. The example below will run 1000 simulations with each simulation taking 5 seconds.

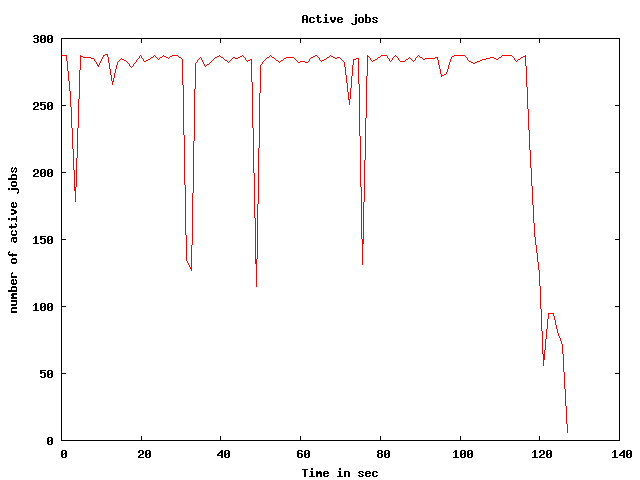

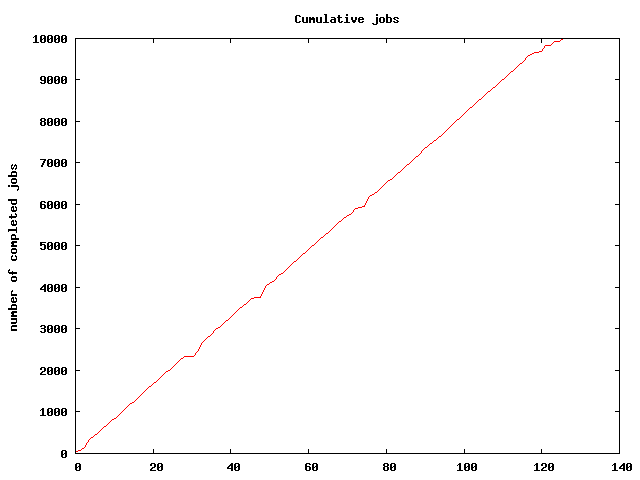

$ swift p6.swift -steps=5 -nsim=1000Plotting run activity

The tutorial bin directory in your PATH provides a script

plot.sh to plot the progress of a Swift script. It generates two

image files: activeplot.png, which shows the number of active jobs

over time, and cumulativeplot.png, which shows the total number of

app calls completed as the Swift script progresses.

After each Swift run, a new run directory is created called runNNN.

Each run directory will have a log file with a similar name called

runNNN.log. Once you have identified the log file name, run the

command plot.sh <logfile>` to generate the plots for that

specific run. For example:

$ ls

output p3.swift run000 swift.properties

$ cd run000/

$ ls

apps cf p3-20131202-2004-0kh4ha6e.d run000.log sites.xml

$ plot.sh run000.logThis yields plots like:

Part 5: Controlling the compute-node pools where applications run

This section is under development.

Part 6: Specifying more complex workflow patterns

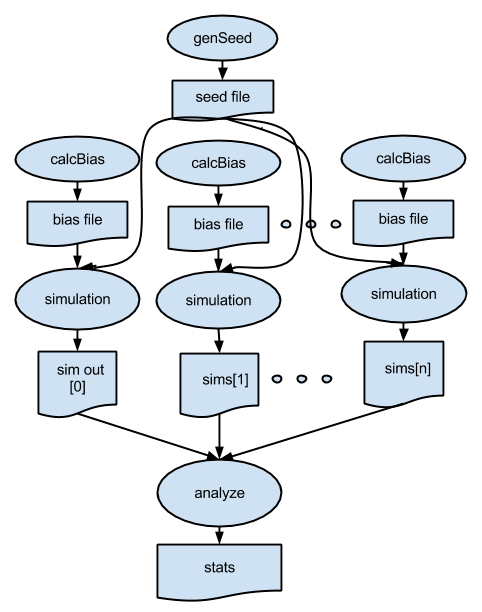

p6.swift expands the workflow pattern of p4.swift to add additional stages to the workflow. Here, we generate a dynamic seed value that will be used by all of the simulations, and for each simulation, we run an pre-processing application to generate a unique "bias file". This pattern is shown below, followed by the Swift script.

type file;

# app() functions for application programs to be called:

app (file out) genseed (int nseeds)

{

simulate "-r" 2000000 "-n" nseeds stdout=@out;

}

app (file out) genbias (int bias_range, int nvalues)

{

simulate "-r" bias_range "-n" nvalues stdout=@out;

}

app (file out, file log) simulation (int timesteps, int sim_range, file bias_file,

int scale, int sim_count, file seed_file)

{

simulate "-t" timesteps "-r" sim_range "-B" @bias_file "-x" scale

"-n" sim_count "-S" @seed_file stdout=@out stderr=@log;

}

app (file out, file log) analyze (file s[])

{

stats filenames(s) stdout=@out stderr=@log;

}

# Command line arguments

int nsim = toInt(arg("nsim", "10")); # number of simulation programs to run

int steps = toInt(arg("steps", "1")); # number of timesteps (seconds) per simulation

int range = toInt(arg("range", "100")); # range of the generated random numbers

int values = toInt(arg("values", "10")); # number of values generated per simulation

# Main script and data

file seedfile <"output/seed.dat">; # Dynamically generated bias for simulation ensemble

tracef("\n*** Script parameters: nsim=%i range=%i num values=%i\n\n", nsim, range, values);

seedfile = genseed(1);

file sims[]; # Array of files to hold each simulation output

foreach i in [0:nsim-1] {

file biasfile <single_file_mapper; file=strcat("output/bias_",i,".dat")>;

file simout <single_file_mapper; file=strcat("output/sim_",i,".out")>;

file simlog <single_file_mapper; file=strcat("output/sim_",i,".log")>;

biasfile = genbias(1000, 20);

(simout,simlog) = simulation(steps, range, biasfile, 1000000, values, seedfile);

sims[i] = simout;

}

file stats_out<"output/average.out">;

file stats_log<"output/average.log">;

(stats_out,stats_log) = analyze(sims);Note that the workflow is based on data flow dependencies: each simulation depends on the seed value, calculated in this statement:

seedfile = genseed(1);and on the bias file, computed and then consumed in these two dependent statements:

biasfile = genbias(1000, 20);

(simout,simlog) = simulation(steps, range, biasfile, 1000000, values, seedfile);To run:

$ cd ../part06

$ swift p6.swiftThe default parameters result in the following execution log:

$ swift p6.swift

Swift 0.94.1 RC2 swift-r6895 cog-r3765

RunID: 20130827-1917-jvs4gqm5

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 19:17:56 -0500

*** Script parameters: nsim=10 range=100 num values=10

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 19:17:57 -0500 Stage in:1 Submitted:10

Generated seed=382537

Progress: time: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 19:17:59 -0500 Active:9 Stage out:1 Finished successfully:11

Final status: Tue, 27 Aug 2013 19:18:00 -0500 Finished successfully:22which produces the following output:

$ ls -lrt output

total 264

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 9 Aug 27 19:17 seed.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_9.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_8.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_7.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_6.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_5.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_4.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_3.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_2.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_1.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 180 Aug 27 19:17 bias_0.dat

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:17 sim_9.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:17 sim_9.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:17 sim_8.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:17 sim_7.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:17 sim_6.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:17 sim_6.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:17 sim_5.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:17 sim_5.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:17 sim_4.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:17 sim_4.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:17 sim_1.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:18 sim_8.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:18 sim_7.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:18 sim_3.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:18 sim_3.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:18 sim_2.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14898 Aug 27 19:18 sim_2.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:18 sim_1.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 90 Aug 27 19:18 sim_0.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14897 Aug 27 19:18 sim_0.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 9 Aug 27 19:18 average.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 p01532 61532 14675 Aug 27 19:18 average.logEach sim_N.out file is the sum of its bias file plus newly "simulated" random output scaled by 1,000,000:

$ cat output/bias_0.dat

302

489

81

582

664

290

839

258

506

310

293

508

88

261

453

187

26

198

402

555

$ cat output/sim_0.out

64000302

38000489

32000081

12000582

46000664

36000290

35000839

22000258

49000506

75000310We produce 20 values in each bias file. Simulations of less than that number of values ignore the unneeded number, while simualtions of more than 20 will use the last bias number for all remoaining values past 20. As an exercise, adjust the code to produce the same number of bias values as is needed for each simulation. As a further exercise, modify the script to generate a unique seed value for each simulation, which is a common practice in ensemble computations.